How the sausage is made, or: How OpenTTD is developed

Ever wondered how a new OpenTTD release is made? How we decide what features to include and what to reject or how some people seem to know the “future” before you? Curious what it means that OpenTTD is Open Source? Or maybe you’ve even wondered what it takes to get your idea included in OpenTTD?

In this post, you’ll get a peek behind the quite transparent curtain and learn more on how OpenTTD is developed.

What’s source anyway?

Let’s start with the meaning of Open Source, as the source (or source code) of a computer program really is the source of it all. In a nutshell, the source code of a computer program is a form that is a lot easier for humans to understand than the instructions the computer is executing. For OpenTTD, we use the programming language C++. This source code is then transformed by a piece of software called a compiler into a binary form that the processor in your device can run. The binary is then combined with various other data files to create the game you can download from our website or for example get via Steam.

While every computer program has a source, not every program is Open Source.

Open Source requires that the source code is freely available and allows modifications by other parties.

You can look at the source code of OpenTTD right now in our git repository on GitHub (but please come back here afterwards).

To be able to track changes to the source code, we use a version control system called git.

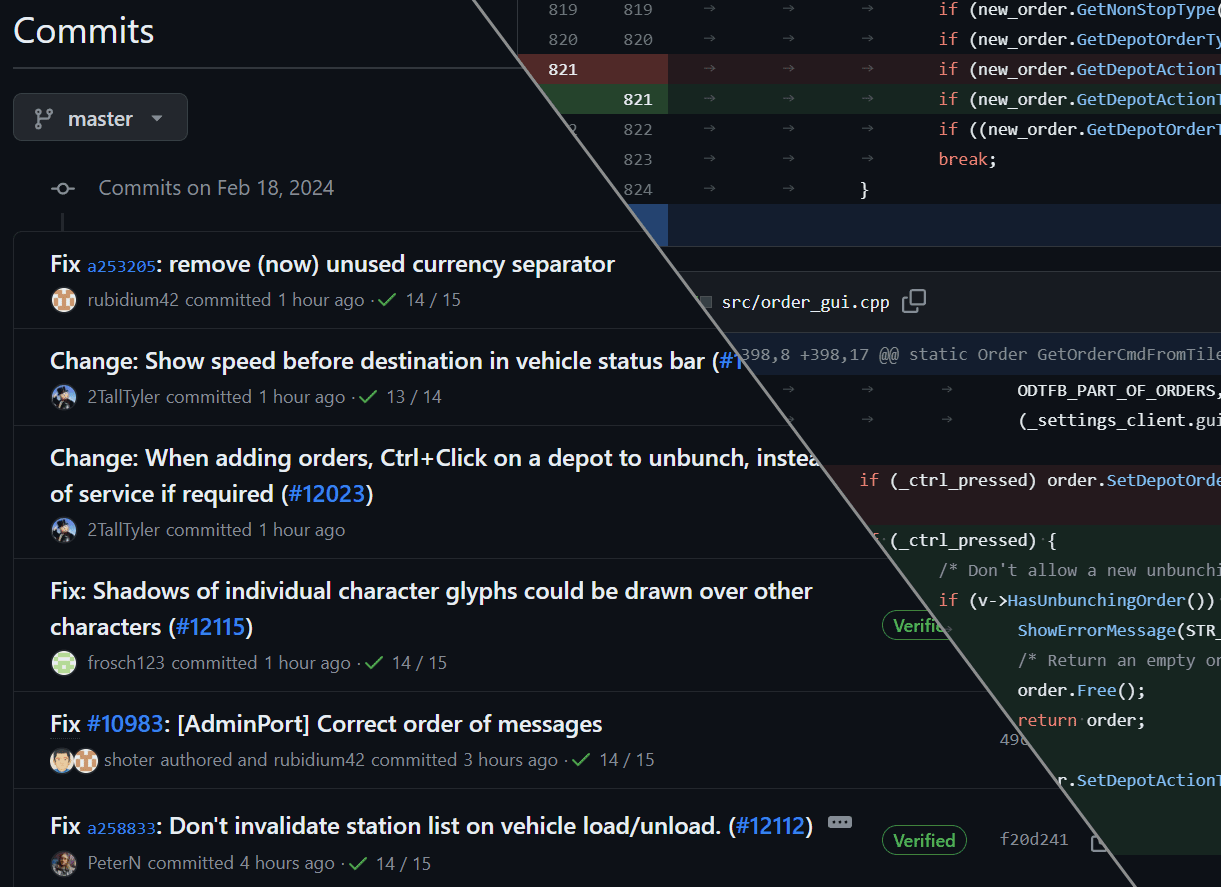

It shows us each and every individual change (called commit in git) that was made to the game since its inception 20 years ago.

Being able to see old changes is quite useful when trying to fix problems or figuring out why something was done the way it was done.

The list of commits is also what you need to watch to gain “magical” knowledge about things that are coming in future releases of OpenTTD.

Our GitHub page is also where things are tracked that are not yet part of the game and still in development. You might have encountered it before as the place where you can report an issue with the game. Besides the git repository of the game itself, GitHub also hosts various other git repositories related to the game, like for example OpenGFX, NewGRF development tools or various back-end infrastructure.

How a feature is born

Now that we know where development happens, let’s look at how it happens.

Each and every change to OpenTTD, no matter if it is a large new feature or just a simple one-line bug fix, starts with someone choosing to spend their time on it. As the source code of the game is freely accessible, this can be literally anyone, for a multitude of reasons.

Many features come about because someone has an idea how their game could be better and decides to work on it. Bugs are usually fixed because someone either feels responsible for it in some way or is just plain annoyed by it. But really, everybody has a different personal motivation. There’s one reason you’re not going to find though: Because the boss said so, or because it is on the big company road map. OpenTTD is purely developed by volunteers, there’s no company, foundation, or other controlling central entity behind it.

Ideas are often discussed in the development channel of the official OpenTTD Discord. It’s a good way to gauge interest, exchange ideas and chat about issues before spending any significant time on something. It’s also a fast way to get help or inspiration when stuck on something while developing for OpenTTD. While activity in the channel does vary over the day, someone is usually always awake.

Now let’s assume that the person is in fact developing a feature (like for example the new ship pathfinder) and has completed the initial development. Since OpenTTD moved to its current home on GitHub almost 6 years ago, we’ve adopted a fixed process for any change to OpenTTD. The first step in the process is to open what is called a pull request (PR) on GitHub with the proposed changes to the source code in the form of git commits. Additionally, we require a description of the changes following a specific template to make sure nothing important is left out.

Whenever a PR is opened, various automatic checks run to verify some formal things, but while those checks are running, other contributors can already begin to review and comment on the pull request. The automated checks include what is called continuous integration (CI), which ensures the PR actually compiles on all platforms we support and not just the one the author is working on.

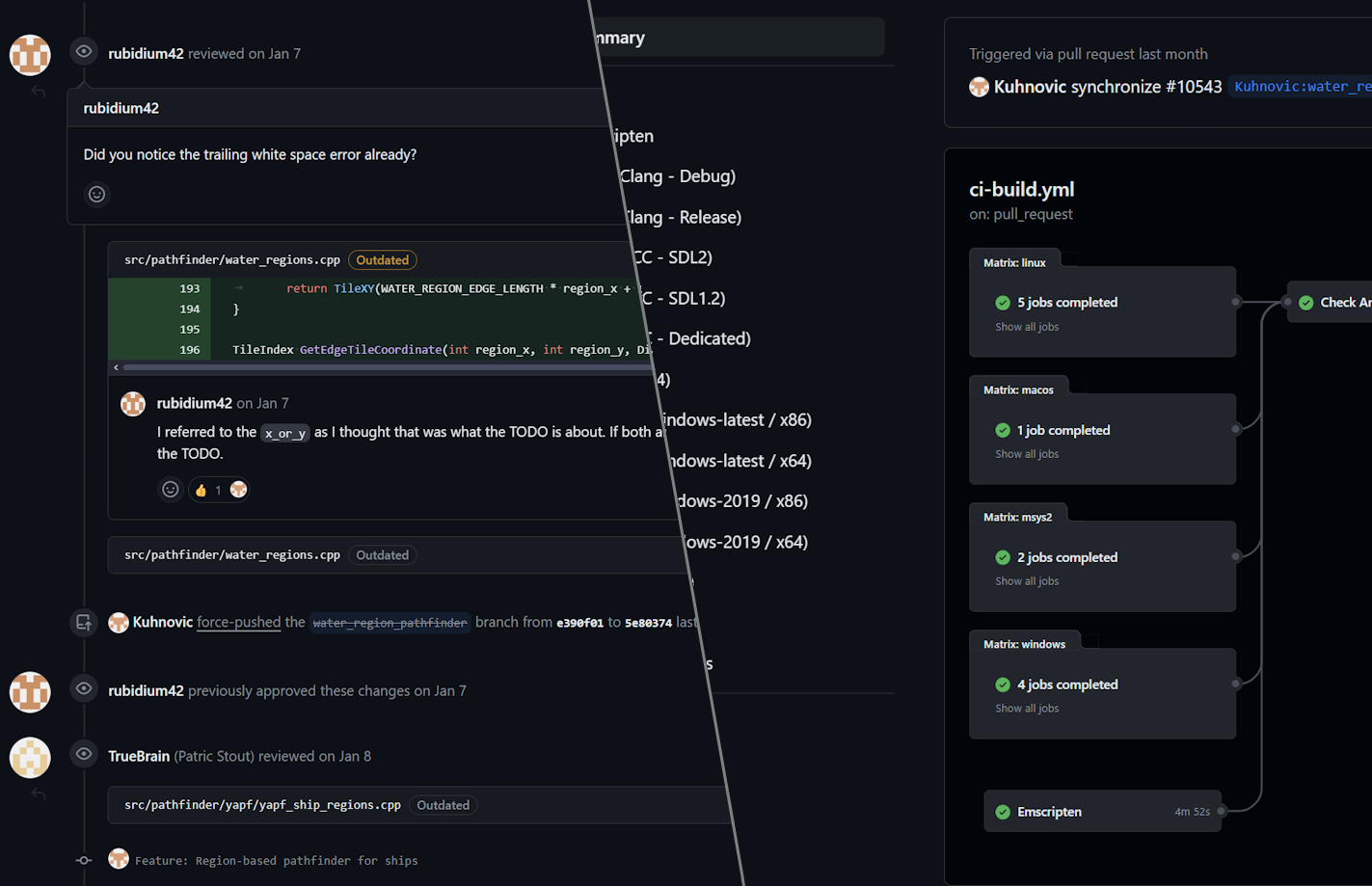

Automated checks are well and good, but so far they can’t replace a human code review. In code review, other people look at the code and try to find any issues or spots that could be improved. This can be everything from validating functionality, checking UI and user experience, to proof-reading code comments. For a large change like the ship pathfinder, we even organized a multi-player test game to check for any dreaded desync problems.

Usually, this results in a back and forth between the author updating the PR and the reviewers looking again until the PR is either declared good or rejected. Unfortunately, not every author has the motivation to follow this until the end, so it happens that PRs just kind of fizzle off without reaching a finished state. Up to here, everybody can pitch in with reviewing a PR, but actually approving or rejecting a PR requires a decision by someone that has commit access to the OpenTTD repository.

PR aren’t actually outright rejected that often. Reasons for rejection might be that the PR is contrary to the goals of the OpenTTD project, like trying to add content that could be very well done as an add-on NewGRF. Sometimes it also happens that a PR is meant well, but just not the right solution for a particular issue because it might affect some other part of the game negatively.

For approving a PR we’re quite strict, maybe stricter than many other projects out there. The OpenTTD project has a rigid code formatting style guide and commit message format. We’re also unlikely to accept a PR with known problems or unfinished parts. For example, the game is translated to many languages, including some that are written right-to-left, and any UI code needs to be coded to work for all languages and not just English. Finally, GitHub will prevent approving a PR if any of the CI checks have failed.

While all this might sometimes appear to be overly pedantic and petty, a strict quality control is important to make sure the game can continue for the next 20 years. Everybody has probably noticed that everything, from your desk to the storage shelf in the shed, seems to always descend into chaos unless cleaned up regularly, and code is no exception to this. If we wouldn’t care about code quality, the source code would probably be a hot mess after 20 years and full of bugs, making any new features really difficult.

One thing of note here is that no author can self-approve a PR, even if they have commit access to OpenTTD. In this sense, all PR authors are treated equal and need to follow the same process to get a PR approved.

Finally, if a PR has the coveted approval, it can be merged into the main code base. This can be done by the person approving it, but especially for bigger changes we like the merge to be done by a second set of eyes. From that point in time it is part of the game, but not yet in the version you are playing right now. For this it still needs a release, which we’ll cover in the next section.

The release process

There are two kinds of releases we make for OpenTTD. The first one is the “nightly”. This is automatically made out of a snapshot of the source code each day. The nightly release uses almost the same CI workflow as described for the PR checks, except that the result is published on our website and on Steam.

The other kind of releases are the interesting ones, the ones that get a proper version assigned, like the upcoming OpenTTD 14.0. These happen whenever we think there are enough new things, improvements, and bug fixes since we made the last major release.

If you’ve been following the news on OpenTTD, you’ll have noticed that we’ve already released some versions with a 14 in it, but yet we’re telling you that 14.0 will come soon. You might ask: What’s up with that? Unfortunately, programmers are just as human as you are, and thus it is very likely that OpenTTD contains numerous bugs at any given time.

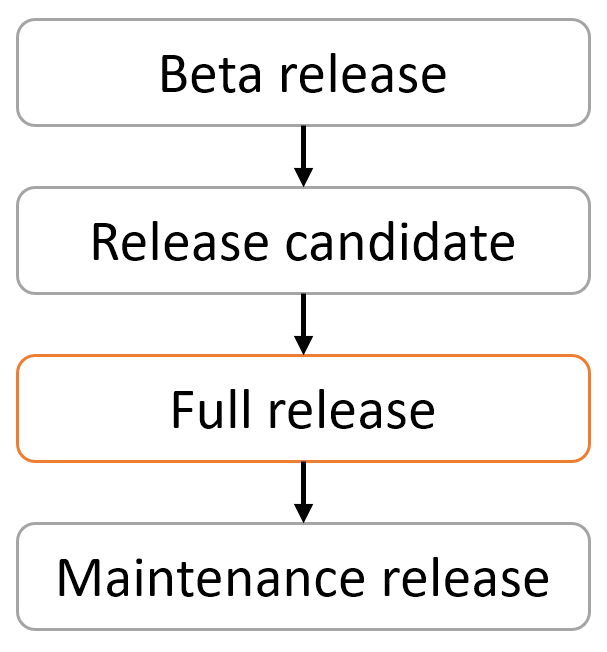

To make sure we can give you the best possible game to play, all major releases follow a specific path, which is shown in the image on the right. It starts with one or more so-called beta releases. A beta release is taken directly from the main source code at a certain point in time. The main purpose of beta releases is to gather feedback from players about new features and to find any issues with the game. Beta releases are still marked as testing releases and are usually not included in Linux distributions or the normal Steam updates, thus depend on players willingly trying a potentially unstable game version.

Even if it’s directly taken from the main source, there’s still a lot of stuff that needs to be done even for a beta release. Someone has to look over all the changes since the last release and write the changelog. The website news post has to be written, posts for social media like Discord or Reddit prepared, and an image for the Steam news post drawn. When everything is ready, a so-called tag is created that marks a specific commit. With this tag, some more automated CI workflows compile binaries for the various platforms we support and upload them to our website and the other distribution platforms. When the CI is done, the news post can be published and the social media posts made so you will actually know that there is a new release.

As it is rare to not find any issues, there are usually multiple beta releases until the number of issues encountered by players drops sufficiently. The next major step in the release process after the betas is branching and feature freeze. Branching means that the source code for the release is split off from the main source code and will no longer automatically track changes made there. Bug fixes are still applied to the branched code, but new features are not. This helps to prevent last-minute problems in the release versions.

After branching, the testing releases continue with one or more Release Candidates (RCs). RCs are similar to the beta version in that issues are still expected, but as no new features are applied anymore, the issue count should go down, not up. The actual release is basically done the same way as a beta: prepare a changelog, all the social news, make a tag, wait for the CI, and finally tell the world.

When no more major issues are found in the latest RC, the time for the first proper release has come. There’s really not much difference in the release process from the RCs, except that this version is not marked as a testing release and thus will be for example picked up by the automatic update on Steam or GOG. We do spend more time on the changelog, news post and social media posts for the release, as a proper non-testing release has a much larger audience than the preceding testing releases.

Inevitably, a larger audience is also better in finding bugs, which is why the maintenance releases exists. Maintenance releases are the X.1, X.2 and so on versions. They do not include new features over the major X.0 release, but fix whatever issues are found.

Thanks to a lot of behind the scenes magic done by some wizards on the CI workflows, the most time-consuming part of any release is actually creating and publishing all the public-facing text and information. Compiling the binary and uploading the result to the various distribution platforms requires surprisingly few mouse clicks to trigger. This wasn’t always the case though. When OpenTTD was still young and sites like GitHub were just not a thing, the various binaries for e.g. Windows, Linux or macOS were hand-compiled by different people, manually collected and uploaded. Often enough that meant that it literally took several days until a release could be downloaded for all platforms. Compared to that, the current automatic CI workflows really do feel like awesome magic.

Getting personal

If you’ve been diligently reading till now, you might have noticed that I haven’t used the word “developer” so far. Instead, I’ve mostly talked about a generic someone. So what’s up with that?

While many people think that the individuals with merge permissions are “the” developers of OpenTTD, this isn’t really true at all. GitHub provides various statistics for each project, and lists 169 contributors to OpenTTD at the time of writing this. And this number is still much too low, as it is for example missing many contributors from before we were on GitHub, and doesn’t count our language translators since their changes are committed by a bot. These hundreds of individuals are the real developers of OpenTTD and the people with commit access are more akin to housekeeping or maintenance.

When you read something like “Why haven’t the devs included X yet?”, it is very rarely because someone with merge permissions said “nope”, even if the questions is often phrased to imply this. It is not included yet because nobody volunteered their time for it.

And that really is the gist of it. OpenTTD is not backed by a big company or some other institution, but purely by volunteer work. OpenTTD depends on donations. This does include monetary donations needed to pay for infrastructure and services, like our website and all the automated systems we’ve described here. But probably even more important, it also includes time donations. And time is what is missing most of time (ahem). So the best way to get X included is to donate some of your time.

Final thoughts

OpenTTD would not have made to 20 years if it weren’t for the hundreds of people that chose to donate some of their time to the project. As such, we are very thankful for everybody who contributed something, no matter how small or big. Without people who contribute code, triage issues on GitHub, make translations, create content like NewGRFs or AIs, or help answer questions on places like the official Discord, Reddit, or Steam forums, OpenTTD would not be where it is right now. And without you playing the game, it wouldn’t be here either.

More about OpenTTD 14

This post is part of the series of dev diaries about big new features coming in OpenTTD 14. Next week, we’ll get a survey of some more behind-the-scenes work that helps us to better understand what players like about OpenTTD.